From the first time Scripture roars with the image of a lion, the symbol of Judah has stirred imagination and hope. To understand why Christians today still speak of Christ as “the Lion of the tribe of Judah,” we must trace the image backward through patriarchal promises, tribal history, royal iconography, and prophetic expectation—then carry it forward into its ultimate fulfillment and present-day power.

A Blessing Spoken over a Son (Genesis 49:8-12).

The phrase bursts onto the biblical scene in Jacob’s dying words to his fourth son. Jacob, once the wandering heir of the covenant, gathers his twelve sons and prophesies over each one. To Judah he declares, “Judah is a lion’s cub… Like a lion he crouches and lies down; who dares rouse him?” In the same breath Jacob foretells a dynasty: “The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until Shiloh comes.” In ancient Near-Eastern culture the lion signified unmatched strength and sovereign rule. Jacob synthesizes the imagery—lion, scepter, staff—so tightly that Judah’s tribal identity becomes inseparable from kingship and fearless power. Immediately, therefore, “lion” means more than raw aggression; it carries covenant promise, territorial guardianship, and a whisper of Messiah.

From Tribal Banner to Royal Standard.

Centuries later, when Israel settles in Canaan, Judah’s territorial allotment encompasses Jerusalem and Hebron. Within this region the young shepherd David slays Goliath, rises through Saul’s court intrigues, and finally ascends to the throne. Scripture never explicitly records a lion emblazoned on David’s shields, but archaeological reliefs from the 9th–7th centuries BC show lions guarding city gates and thrones throughout the Levant, and later rabbinic tradition identifies the lion as Judah’s ensign. Whether painted on a war banner or simply lodged in collective memory, the roaring emblem clung to David’s line—an enduring reminder that every king of Jerusalem owed his legitimacy to Jacob’s prophetic blessing.

Exile Could Not Silence the Lion.

When Babylon toppled Jerusalem in 586 BC, skeptics might have concluded the Judah-lion had been muzzled. Yet the prophets doubled down. Ezekiel envisions a future Davidic shepherd-prince. Isaiah pictures a shoot from Jesse’s stump on whom the Spirit of the Lord rests. Even in lament, Jeremiah remembers a covenant that will restore “the righteous Branch.” Far from fading, the lion symbolism intensified: Judah’s monarchy would return, but on grander, everlasting terms.

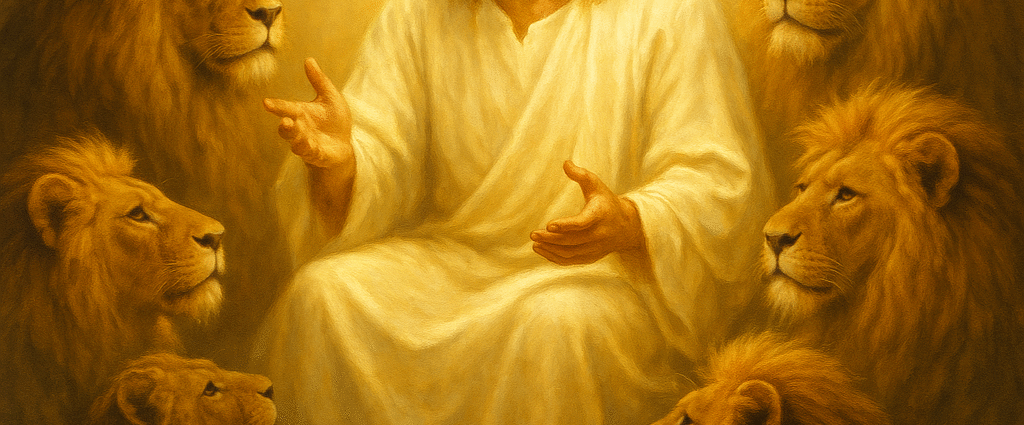

A Title Fulfilled in Jesus.

Fast-forward to the first century. Matthew and Luke open their Gospels with genealogies anchoring Jesus firmly in Judah’s line through David. The Gospels paint Him as both shepherd and king, gentle with children yet unflinching before tyrants. After Calvary and Easter, the apostolic Church sifts its Scriptures for language big enough to frame His victory. In Revelation 5 the apostle John weeps because no one is worthy to open the scroll of human destiny—until a heavenly elder proclaims, “Behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed.” John looks, expecting a predator, and sees a Lamb standing as though slain. The paradox is deliberate: the Lion’s conquest came through sacrificial meekness. Power, holiness, and love fuse in one figure; the symbol’s circle is complete.

Echoes beyond Israel.

The lion of Judah did not remain confined to Jewish lore or early-Christian preaching. Ethiopia’s Solomonic emperors traced their lineage to the union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, styling themselves Moʿa ʾAnbäsa Zä Yǝhuda—“Conquering Lion of the tribe of Judah.” Medieval Crusaders embroidered lions on capes to signal devotion to the Davidic Messiah. In the Caribbean and African diaspora, the Rastafari movement adopted the “Lion of Judah” to express both messianic yearning and cultural resilience. Each appropriation testifies to the symbol’s magnetic authority, though only Scripture weds that authority to the crucified and risen Christ.

Theology in a Single Roar.

Why does the image still resonate? Because the lion unites attributes modern hearts often separate. We crave leaders who are kind yet strong, approachable yet un-intimidated, defenders of the weak yet terrors to evil. Judah’s lion meets that composite ideal. He embodies (1) Sovereign Authority—the right to rule grounded not in politics but in divine promise; (2) Protective Courage—the readiness to attack whatever threatens God’s people; (3) Majestic Purity—a holiness that provokes awe; and (4) Sacrificial Love—a willingness to die for the flock. No mere human dynasty, slogan, or movement can sustain all four without fracture. Christ alone holds them in perfect tension.

Practical Implications for Today.

For believers confronting a culture awash in uncertainty, the Lion of Judah offers steadying clarity. His roar reminds parents that godly authority in the home is both tender and unyielding. It emboldens pastors—like the reader of this blog—to preach truth without apology, confident that ultimate victory belongs to the King we serve. It strengthens activists laboring for justice, assuring them that the moral arc of history bends beneath a Lion-Lamb who has already secured a righteous end. And it comforts the suffering: if the Lion who conquered death calls you His own, then no earthly predator, be it cancer, recession, or persecution, can ultimately devour you.

Looking Ahead—Hearing the Roar.

But symbols—even sacred ones—can slip into nostalgia unless they are practiced. So let the old tribal emblem awaken new disciplines:

- When you open Scripture tomorrow morning, listen for the Lion’s voice in every promise of protection and every summons to holiness.

- When you gather with your church, sing as though a regal presence truly walks the aisle.

- When you face injustice, speak with fearless integrity, knowing the Lion has your back.

- When you craft sermons, blog posts, or daily conversations, refuse both sentimental fluff and cynical despair; aim instead for the courageous hope that marks Judah’s greatest Son.

Conclusion.

The Lion of Judah is not a mythic beast roaming a forgotten desert; He is the resurrected Christ reigning now and returning soon. His roar shook the gates of hell, His paw crushed the serpent’s head, and His mane still shines with covenant faithfulness. Stand beneath that banner, teach it to your children, emblazon it on the core of your ministry, and you will find that courage and compassion no longer feel like opposites—they feel like home.

So, dear reader, pause a moment. Picture that lion—majestic, scarred, victorious—and hear Him call you by name. Then step forward in faith, for the same Lion who guarded Judah guards you, and His roar still echoes through every chapter of redemption history, inviting you to live boldly, love deeply, and lead with unbreakable hope.